The Fire That Barbecues Us From the Inside

About the Author

Dr. Corina Ianculovici, DNP, FAAMFM, ABAAM-HP, is a board-certified advanced practice clinician specializing in

longevity medicine, metabolic health, and hormone optimization and functional aesthetics.

She is the founder of Mirelle Institute for Anti-Aging Medicine in New Jersey.

Why Inflammation Is Never Local—and Almost Never Harmless

Why a sore knee, a tired liver, or low energy is rarely “just that”

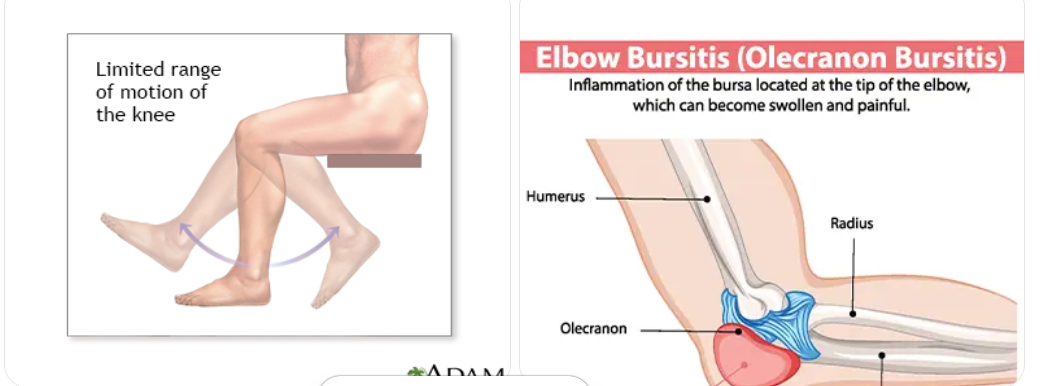

Most people notice inflammation only where it hurts.

- A stiff knee.

- An aching elbow.

- A shoulder that suddenly feels stiff.

- A waistline that refuses to flatten despite effort.

- Persistent fatigue.

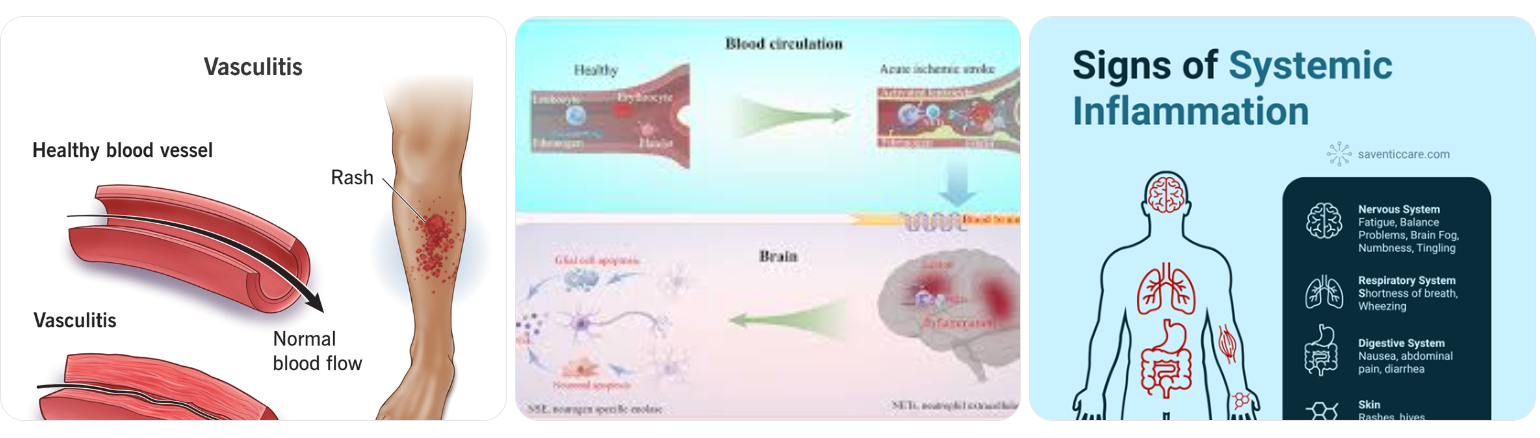

But inflammation rarely stays in one place. Once it begins, it moves through the bloodstream, affecting organs, blood vessels, and the brain. What feels like a local problem is often part of a larger, systemic process unfolding quietly over time.

Chronic inflammation has been linked to heart disease, metabolic dysfunction, fatty liver disease, cognitive decline, and accelerated aging. It does not announce itself dramatically. It builds slowly, often without symptoms, until the damage is harder to ignore.

Most people dismiss these changes as mechanical—age, overuse, “just arthritis.” Something local. Something contained. A pulled muscle.

They are not. They are often the earliest visible signs of a systemic process that rarely announces itself until the damage is advanced:

chronic inflammation.

When the body is quietly burning from the inside

You may feel it as a sore knee, a stiff elbow, or lingering fatigue. But inflammation rarely stays where you notice it.

Once it begins, it travels—through the bloodstream, into organs, blood vessels, and the brain. What feels like a local issue is often part of a much larger story unfolding system-wide.¹

Chronic inflammation has been linked to heart disease, diabetes, liver disease, cognitive decline, and accelerated aging. It does not announce itself loudly. It accumulates slowly, silently, and steadily.²

Pain Is the Smoke. Inflammation Is the Fire.

Inflammation does not stay where it begins.

When it appears in a joint, it has often already passed through the vascular system, the liver, and the brain, impairing cellular communication and energy production along the way.

The knee hurts because it can.

The heart and brain do not—until they fail.

This is why arthritis, cardiovascular disease, fatty liver disease, neurodegeneration, and cancer frequently coexist. They are not separate conditions. They are different expressions of the same underlying biology.

Inflammation Is a Whole-Body Event

This Is What Under-Fueled, Stressed Mitochondria Look Like in Real Life

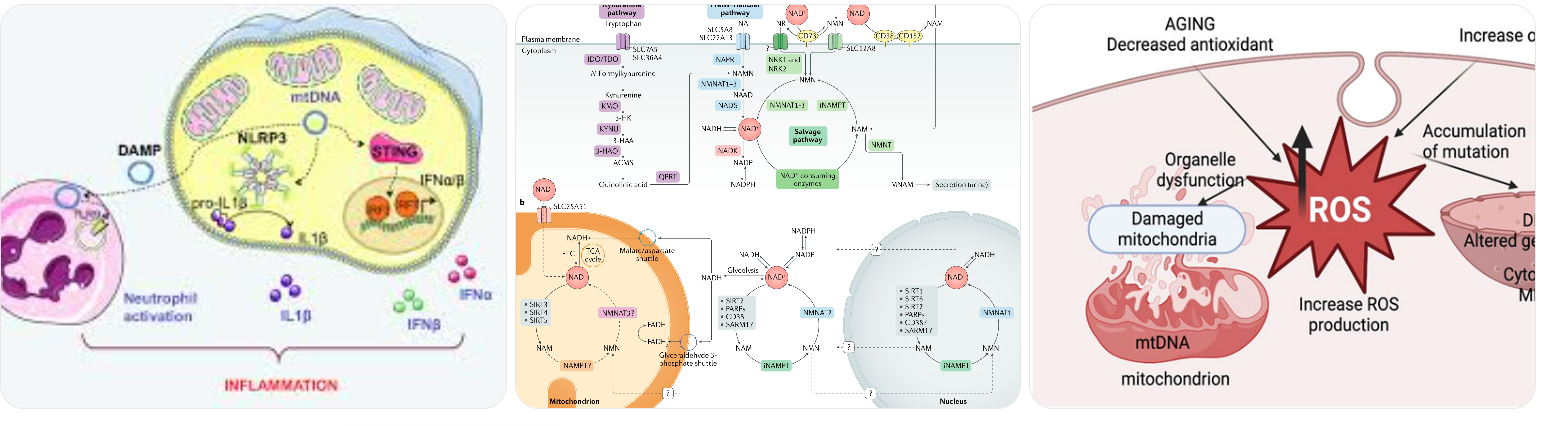

Mitochondria are the parts of your cells that make energy. When they are healthy, your body repairs itself, manages inflammation, and adapts to stress.

When mitochondria are under-fueled or chronically stressed, energy production drops. Repair slows. Inflammation becomes the background state of the body rather than a short-term response.

The most dangerous part? For years, it doesn’t hurt. Cells adapt by doing less. Tissues age faster. Damage accumulates quietly. By the time symptoms appear, this process has often been active for many years and is mistakenly labeled “normal aging.”

Mitochondria are the cell’s energy centers, the power house. When they are well-fueled, cells repair, renew, and protect themselves. When they are stressed—by inflammation, poor metabolic signaling, or declining cellular nutrients—energy drops, repair slows, and damage accumulates.³ In simple terms, the power is out.

The most dangerous aspect? For years, it doesn’t hurt.

Under stress, mitochondria shift into survival mode. Energy production becomes less efficient. Inflammation becomes the background noise of daily life. Aging accelerates—not because time passes, but because repair no longer keeps up with damage. By the time symptoms appear, this process has often been underway for a decade or more.⁴

Low-grade, chronic inflammation circulates silently, disrupting:

- Endothelial function (how blood vessels respond and dilate)

- Cerebral blood flow (how the brain maintains clarity and memory)

- Insulin signaling (how fat accumulates and energy is stored)

- Immune surveillance (how abnormal cells are detected and removed)

A sore elbow is rarely just an elbow. It is often the loudest messenger of a quieter systemic story.

The Damage You Don’t Feel—Until You Do

This Is Not an Alcoholic’s Liver

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is now one of the most common metabolic conditions worldwide.

It affects people who eat “healthy,” exercise regularly, and rarely drink alcohol. Fat accumulates silently in the liver, disrupting insulin signaling, increasing inflammation, and raising long-term risk for cardiovascular disease and cognitive decline.

Most people feel nothing until damage is advanced.

The absence of pain does not mean the absence of disease.

Many of the most consequential inflammatory conditions are painless in their early stages.

Consider what chronic inflammation looks like before symptoms appear:

- Fatty liver disease , often discovered incidentally on ultrasound, with no discomfort until fibrosis develops

- Actinic keratoses , a field of sun-damaged skin that represents pre-cancerous change

- Basal cell carcinoma, slow-growing and often ignored until tissue damage is visible

- Melanoma , the form of skin cancer that changes life expectancy when detected late

This is what under-fueled, stressed mitochondria look like in real life.

The most dangerous aspect is not how it looks—but how quietly it progresses. Under-fueled, chronically stressed mitochondria adapt by lowering energy output, prioritizing survival over repair. In this state, tissues age faster, inflammation becomes normalized, and cellular damage accumulates below the threshold of pain or alarm. By the time symptoms appear, the process has often been unfolding for years—unnoticed, unmeasured, and mistakenly dismissed as “normal aging".

The most dangerous aspect? For years, it doesn’t hurt.

The Cellular Missing Link: Intracellular NAD⁺

At the center of inflammatory control is not a joint, an organ, or a lab value—it is the cell.

And one of the most critical intracellular molecules governing inflammation, repair, and energy is nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD⁺).

NAD⁺ is essential for:

- Mitochondrial energy production

- DNA repair and genomic stability

- Regulation of inflammatory signaling pathways

- Cellular survival under metabolic and oxidative stress

Peer-reviewed research consistently shows that NAD⁺ levels decline with age, while inflammatory burden increases. As NAD⁺ falls,

cells lose the ability to regulate stress and repair damage efficiently.

Suppressing inflammation without restoring NAD⁺ is akin to turning down a smoke alarm while the fire continues to burn.

When Statistics Replace Stories

On a population level, this silent biology becomes visible in the data.

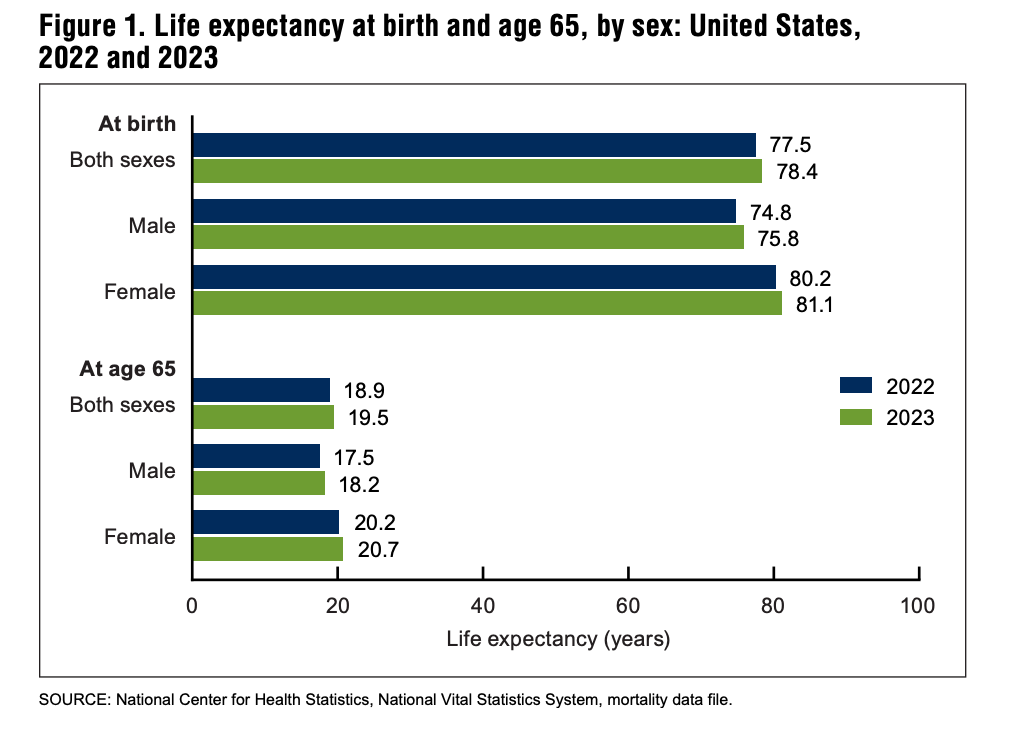

In the United States, life expectancy remains under 80 years. At age 65, the average person has fewer than 20 years remaining. Many of those years are lived with chronic disease rather than vitality.

These outcomes are rarely caused by sudden illness. They are shaped by long-term inflammation, metabolic stress, and declining cellular energy that go unaddressed for decades.

What begins quietly often ends statistically.

Public health data make one point clear: risk accelerates sharply after midlife, driven largely by inflammatory and metabolic disease—not sudden events.

Life expectancy tables published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention demonstrate a steady rise in all-cause mortality with advancing age, largely attributable to cardiovascular disease, cancer, and neurodegenerative conditions.

CDC Life Tables (2024–2025) speak volumes. Averages are comforting. But averages are made of individuals who waited.

The relevant question is not “ What happens to most people?”

It is “ Do I want to manage my biology—or become part of the curve? ”

The Mirror Test

Look at your hands.

The texture of your neck.

The way your joints move.

The speed at which you recover.

...Nothing needs to be said.

Your biology is already keeping score.

Taking Control vs. Becoming a Statistic

This is not about fear. It is about agency.

At Mirelle, NAD⁺ therapy is used as part of a broader, clinically guided strategy to restore intracellular capacity—supporting mitochondrial function, regulating inflammation, and improving resilience at the cellular level.

For individuals who prefer structure over guesswork, our Private Longevity Concierge Membership offers discreet, personalized oversight for those who invest intentionally in long-term health, youth, and performance.

This is not episodic care.

It is designed longevity.

The fire can be quieted.

But only if it is addressed before it takes something you cannot get back.

References:

Blaut, M., & Klaus, S. (2012). Intestinal microbiota and obesity. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, 209, 251–273.

Campisi, J., Kapahi, P., Lithgow, G. J., Melov, S., Newman, J. C., & Verdin, E. (2019). From discoveries in ageing research to therapeutics for healthy ageing. Nature, 571(7764), 183–192.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Mortality in the United States, 2023 (NCHS Data Brief No. 521). National Center for Health Statistics.

Chalasani, N., Younossi, Z., Lavine, J. E., et al. (2018). The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology, 67(1), 328–357.

De Cabo, R., & Mattson, M. P. (2019). Effects of intermittent fasting on health, aging, and disease. The New England Journal of Medicine, 381(26), 2541–2551.

Finkel, T., Holbrook, N. J. (2000). Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature, 408(6809), 239–247.

Franceschi, C., Garagnani, P., Parini, P., Giuliani, C., & Santoro, A. (2018). Inflammaging: A new immune–metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 14(10), 576–590.

Kirkland, J. L., & Tchkonia, T. (2017). Cellular senescence: A translational perspective. EBioMedicine, 21, 21–28.

López-Otín, C., Blasco, M. A., Partridge, L., Serrano, M., & Kroemer, G. (2013). The hallmarks of aging. Cell, 153(6), 1194–1217.

Martínez-Reyes, I., & Chandel, N. S. (2020). Mitochondrial TCA cycle metabolites control physiology and disease. Nature Communications, 11, 102.

Ruan, H. B., & Xu, C. (2019). Regulation of telomerase activity and telomere maintenance by metabolism. Trends in Biochemical Sciences, 44(4), 317–331.

Verdin, E. (2015). NAD⁺ in aging, metabolism, and neurodegeneration. Science, 350(6265), 1208–1213.

Younossi, Z. M., Golabi, P., Paik, J. M., et al. (2019). The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology, 69(6), 2672–2682.